By Traci Donnelly

Chief Executive Officer

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted young people’s mental health—and adults’, too, if we’re being honest—so the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Day theme of making mental health and well-being for all a global priority could not have come at a better time.

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted young people’s mental health—and adults’, too, if we’re being honest—so the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Day theme of making mental health and well-being for all a global priority could not have come at a better time.

If you are struggling with your mental health, you are not alone. Mental and public health professionals of all nations and cultures are reporting that their clients are feeling overwhelmed, uncertain, anxious, helpless, frustrated, stressed, and exhausted. Not surprisingly, these emotions are leading to a decrease in frustration tolerance and an increase in anxiety, depression, and substance abuse.

At The Child Center of NY, we serve a truly global population. We are headquartered in Queens, the nation’s most diverse large county. And as an organization that began as a children’s counseling center, mental health is the heart of everything we do. In the past two years, we have seen a devastating increase in young people of all backgrounds presenting with significant mental health challenges. Whereas we used to get 3-5 high-risk, high-need cases a week, we now get 3-5 a day. We have increased services by 15 percent in these years, translating to 200 more services per week.

And these are people who are seeking—and getting—the care they need. Citywide, one in five New Yorkers is experiencing mental illness, yet hundreds of thousands of these New Yorkers are not connected to care. The services, skills, and funding for mental health are just not keeping up with demand, especially in low- and middle-income communities. As we at The Child Center know firsthand, access to mental health care disproportionately affects New Yorkers depending on their race, ethnicity, gender, insurance status, and the poverty level of their neighborhood. Clearly, more funding and training for culturally responsive behavioral health care is needed for system transformation to occur.

As we continue fighting for funding that is consistent with need, here are five ways that governments, care providers, schools, and other stakeholders can truly make mental health a priority now.

- Start early, on two levels: On the individual level, start before a challenge becomes a crisis; and on the systemic level, start early in childhood—ideally before children are even born.One way to start early on both levels is by reaching families at non-mental health entities.Hospitals are one such place. For example, The Child Center partners with a local hospital, NYC Health + Hospitals/Elmhurst, to educate staff and patients who have recently given birth about signs of postpartum depression.

Child Center Perinatal Infant Mental Health Consultant Terry Gomez, Ph.D., with Congresswoman Grace Meng at an event at Health + Hospitals/Elmhurst. Learn more: .

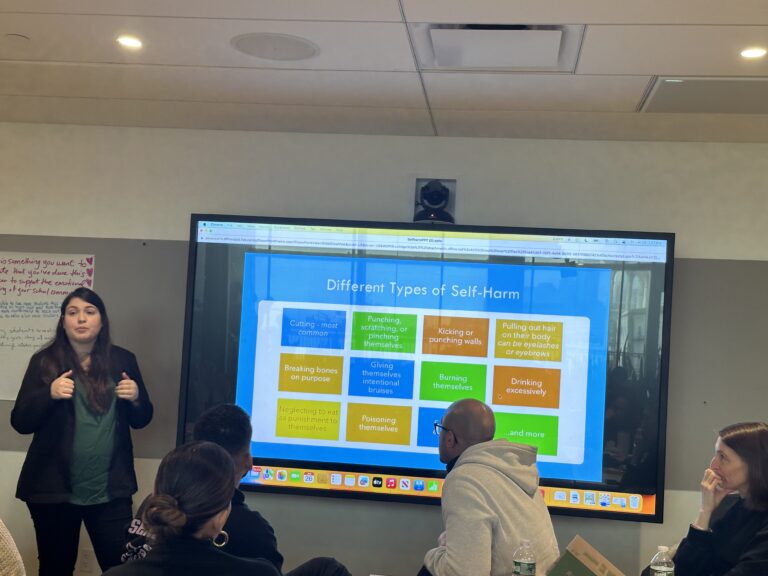

Schools are another. We provide outreach to every kind of educational entity, from preschool to high school. At The Child Center’s own Early Head Start/Head Start centers, educators are trained in emotionally responsive teaching, and every family is assigned a family worker, trained to recognize needs for services. Centers even have on-site social workers, who also serve as mental health consultants to non-Child Center early childhood programs in shelters and other community settings, thereby expanding our reach.In public elementary, middle, and high schools, our school-based mental health wellness centers help schools make mental health an integral part of education, as well as provide therapy and other services for those who need it. We provide psycho-social education to teachers and other school personnel so that they can refer students for mental health services at early stages—again, before a challenge becomes a crisis.

Once issues are identified, we need to ensure targeted services are available. The Child Center recently launched a perinatal program for pregnant people and new moms with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (a.k.a., postpartum depression), and our Early Childhood Mental Health initiative serves families with children ages 0-5 with evidence-based, trauma-focused models of treatment that have been proven to make a difference for this age group and give them the promising start we want for all our children. Just as we need to ensure that children begin school academically ready to learn, we also need to ensure they begin life socially and emotionally ready to thrive.

- Speak the same language—literally and figuratively. If we are talking about making mental health a global priority, we need to think about how we reach people from different cultures. There is no cookie cutter approach. At The Child Center, we hire clinicians and other team members who not only speak the same literal language, but also share lived experiences with clients, which makes clients more likely to confide in them and trust their guidance—and makes it more likely for us to reach them in the first place. For example, we serve a large Asian immigrant population. A lot of the outreach we do is through schools, since many of the parents in these communities place a high value on education. Teachers are often the most effective messengers to recommend mental health services. We also keep in mind generational differences. While American-born teens may be savvy to the fact that mental health is important, their parents may be from a different part of the world, where mental health treatment is surrounded by stigma. At our Woodside and Flushing Wellness Centers, 80 percent of our clinicians are bilingual and bicultural; many have been raised in those same communities. We have the capacity to bridge the gap between generations and

serve as a conduit between those born here and their parents.

serve as a conduit between those born here and their parents. - Teach coping skills. Young children used to learn to regulate themselves through play and social situations. Their ability to adopt coping skills learned and practiced in school and social settings was severely limited by restrictions, remote learning, and parents working from home during the pandemic. Parents may need help teaching their children coping skills that they haven’t learned before.

With older children, social media of course is a factor, as is the anxiety of returning to school after an extended period of isolation. School-age children and teens are readapting to school and social life, and it has been a big adjustment. Some individuals are able to cope with it. Some need to learn how to do that, and families should know that this is something therapy can help with. - Make services truly accessible. There are so many ways we can do this:

- Offer services right in the neighborhoods where people live. If you tell a struggling single mom with multiple jobs and kids that her child needs therapy and refer her to a clinic in an unfamiliar neighborhood where they may or may not speak the same language and is accessible only by subway with a transfer to a bus and requires buying MetroCards for each visit… can we really say those services are “accessible”?

- Offer services for all ages under one roof. Some clinics serve only children, some serve only adults. Some serve mental health needs but not physical health needs, or vice versa. Offer one-stop shops in people’s own neighborhoods, and you have lifted a heavy burden from them—and increased the likelihood of their receiving needed services.

Valerie (center) and her son (bottom row) receive services at our newly renovated Jamaica Family Wellness Center, which offers comprehensive services that range from behavioral and primary health care to benefits access. Also pictured: Nurse Taylor Drew (left) and Dr. Nicole Brown (right).

- Offer services where people are already. The Child Center operates an Early Childhood Mental Health satellite at our Head Start centers. Our school-based mental health wellness centers are located right in public schools. Students can attend therapy during the school day.

- Offer services through tele-health. This means making sure both therapist and client have the technology and training—and the training is in a language the client understands. We have had a lot of success with this. Even tech-averse clients have thrived: After instituting tele-therapy, services became significantly more accessible and our broken appointment rate decreased from 24 percent to 17 percent.

- Make it easier for clients to pay. A lot of providers do not accept Medicaid. Often, families very much want to take their children to therapy, as a teacher or doctor has recommended, but their only insurance is Medicaid—and they cannot find a provider who will accept it. Governments, providers, and other stakeholders need to work together to eliminate this barrier to treatment.

- Show clients you value them. The Child Center’s three wellness centers have been recently renovated—and wow, does it make a difference. A client comes into a bright, clean, welcoming space and immediately feels more comfortable. If a place is rundown, dirty, and poorly lit, they don’t want to be there any more than you would. A high-quality space shows people that you value them, and that you know they are worthy of the highest quality environment and care.

- Change the narrative. This is something in which we all can play a role. We can make mental health a priority by talking about it openly and seeking help when we need it—or even think we might. People go to their doctor not just when they think they might be having a heart attack, but when they are not sure if that sore throat is due to a common cold or might be strep or something else. A parent of a teen will likely seek help if they think their child is suicidal—but they should also feel comfortable seeking help if they are not sure if their child is just feeling a bit down or might have depression or are simply having a tough time handling everyday stressors. We can prevent so much heartache and squandered potential by seeing and talking about mental health for what it is: a crucial part of a healthy life.