By Renée Riebling, Senior Communications Specialist

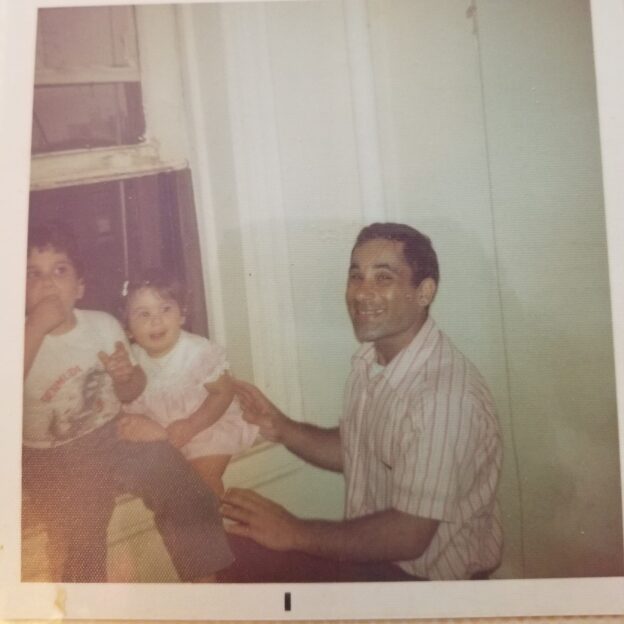

The blog author (center) with her brother and father in an undated photo. Note: Do not try this at home!

May is Jewish American Heritage Month, and for most Americans, that means Ashkenazi Jewish: bagels and lox, Fiddler on the Roof, immigrants from Poland, Russia, and Germany at the turn of the 20th century.

For most of my life, that’s what it meant for me, too. When I was a child, my family lived in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn, where most of our apartment complex’s residents—including my mother—were descendants of Jews from Eastern Europe or had immigrated from the region themselves. We really did eat bagels (though some renegades opted for bialys) with cream cheese and lox on Sunday mornings. We saw Fiddler on the Roof when a production came around, and we saw our ancestors in the characters and storylines. My most treasured childhood memories are of Passover seders, which always were raucous affairs at my aunt and uncle’s house in New Jersey with spirited singing in celebration of the ancient Israelites’ exodus from slavery in Egypt to freedom.

But there were pockets of my life that were a different kind of Jewish. Instead of bagels and lox, this kind of Jewish involved amba and bamia, foreign languages, and trips to a store on Atlantic Avenue that smelled of exotic spices and felt like home. That’s because my father is, as I’ve come to understand, Mizrahi. But in those days before the internet, I didn’t have a name for it. I just knew my father was born in Iraq, which made us different. I knew my father’s family had lived there since the Babylonian Exile more than two thousand years ago until 1950, when they were forced to flee. My father was nine years old at the time. They had to leave in secret and in disguise, and his older brother was held for ransom by former friends who had promised to help him escape safely. Despite this, they miraculously all made it to Iran—which was friendly (or, friendlier) to Jews at the time—and from there, boarded a flight to Israel, where my father lived until he left for Canada in 1964 and then to the United States.

Unlike the fathers of my friends, my father spoke two other languages (Arabic and Hebrew)—languages he intentionally did not pass on to my brother and me so we would be more “American.” I wrote letters to Savta, my grandmother in Israel, on flimsy blue airmail paper that folded into its own envelope (this fascinated me). She always wrote back in beautifully handwritten, flowery English, as she had been an English teacher. My father’s older brother sent photos of his children—my cousins, whom I had never met but looked more like me than anyone else in my life—and I couldn’t stop staring at them.

Although my parents’ decision to raise us to speak only English was a missed opportunity (hindsight is indeed 20/20), the intricacies of language and immigration had a profound impact on me. I was forced to think deeply about language because my father peppered me with questions about it.

When I was in kindergarten, my class had to memorize the first verse of “My Country ’Tis of Thee.” I sang it proudly for my father, pleased with myself that I knew all the words. When I finished, I thought he was going to gush about my expert singing and memory. Instead, he asked, “What is ‘thee’?”

“What?” I said back.

“What is ‘thee’?” he repeated. “You said my country ‘’tis of thee.’ So, what is ‘thee’? What is the country of?”

I was 5 and didn’t know the answer. I had never thought about the meaning of the lyrics. The question haunted me. What exactly was this “thee” our country was made of? And why was I singing something I didn’t understand?

He often asked questions like this, and it set me on a lifelong quest to understand language, to appreciate the importance of finding the most precise word, and to always subconsciously work to understand connotation and nuance.

(Fun fact: I now understand that “thee” in “My Country ’Tis of Thee” is the country, and it’s a lesson in the importance of grammar! If you look at how the song is written—“My country, ’tis of thee, [s]weet land of liberty, [o]f thee I sing”—the commas make clear that the songwriter is addressing his country, and “thee” is the “sweet land of liberty,” a phrase used to describe “my country.” Fascinating!)

I recently read somewhere that children of immigrants, as well as those who immigrated when they were children, are more likely to become writers. In my own family, I discovered that the pull to understand language was a shared pursuit. In addition to my grandmother being an English teacher, my great-uncle wrote what is considered the first definitive Arabic-Hebrew dictionary.

I also learned from my father the importance and irreplaceability of both nonprofit organizations (a nonprofit was responsible for his being able to escape Iraq) and social workers—both core parts of The Child Center. One of my father’s most vivid childhood memories is of the day at school when he was wearing short pants in cold weather and a social worker took notice. She knew it was because his family could not afford long pants, and she got a pair for him. Even seventy-five years later, he vividly recalls the social worker’s warmth and sincerity—how he felt an instant sense of trust in her, and how she became an essential pillar of support in his life. I am often reminded of this story when I write about The Child Center of NY’s School-Based Mental Health initiatives and the clients who find support in the therapists embedded in their schools. I guess it is no surprise I ended up being not just a writer, but a writer for a nonprofit dedicated to mental health!

But above all, perhaps my father’s greatest gift to me is an appreciation of people’s different perspectives and life experiences and all they bring to the table.

At one of my former workplaces, a new intern aroused suspicion because he seemed impossibly nice and upbeat. It must be fake, some people thought. “You got it!” he’d say when you asked him to do something. When the task was completed, he’d inquire, “Was everything done correctly?” When you thanked him, he’d reply, “Glad to help!”

It turned out he had grown up in Detroit with a single mother who worked extremely hard to make ends meet. He’d been mistaken for “someone who did something” more times than he could count. But here he was, he’d said, a student at an Ivy League college with an internship working for a premier nonprofit. He couldn’t believe how lucky he was and resolved never to take one thing for granted. He reminded me of my dad. Though their origins were very different, this young man was a hardworking, intelligent, and caring human trying to make it in a different kind of world than the one he’d grown up in, and everyone who knew him was richer for the experience.

As we celebrate Jewish American Heritage Month this year, it’s with the knowledge that now is a difficult time to be Jewish. In 2024, Jews were the target of 54 percent of all recorded NYC hate crime incidents. Sadly, this reflects a national and even worldwide trend of increasing antisemitism. But like all people who have cultural histories of persecution and hate, I know that the antidote is joy. As my ancestors have for generations, we find joy in our traditions and resilience.

These days, our Passover seders take place either in my home or at the home of a cousin—whose parents, my aunt and uncle, hosted them when I was growing up. We sing the same songs and recite the same passages we sang and recited when I was young, and that Jews have been singing and reciting for thousands of years. My Israeli cousins are no longer the faces of strangers in faded photographs. I’ve gotten to know them, and they are some of the kindest, most genuine, and most resilient people I have known. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we participated in a Zoom seder with them. They had some different melodies to the same songs that my Ashkenazi family sang, and I felt immense pride in being part of both these legacies.

I love that The Child Center takes heritage months seriously and uses them to celebrate the fact that our diversity is one of our greatest blessings.