Mehak Mahmood is a Program Director at our SONYC afterschool program at J.H.S. 185 Edward Bleecker Middle School, in Flushing, Queens. She has been with The Child Center for more than a decade, and has served at J.H.S. 185 for eight years. This month, we had the opportunity to speak with her about Ramadan. For the Muslim community, Ramadan is one of the holiest months of the year, marked by abstaining from food and water from sunrise to sunset. It is a time to deepen faith, cultivate self-discipline, and give back to the community.

Mehak Mahmood is a Program Director at our SONYC afterschool program at J.H.S. 185 Edward Bleecker Middle School, in Flushing, Queens. She has been with The Child Center for more than a decade, and has served at J.H.S. 185 for eight years. This month, we had the opportunity to speak with her about Ramadan. For the Muslim community, Ramadan is one of the holiest months of the year, marked by abstaining from food and water from sunrise to sunset. It is a time to deepen faith, cultivate self-discipline, and give back to the community.

The Child Center of NY: Ramadan Mubarak! How are you observing Ramadan this year at J.H.S. 185?

Mehak Mahmood: During my time at J.H.S. 185, I’ve always offered a designated area for Muslim students who wish to perform one of the five obligatory prayers or salah during school hours. This space is clean, equipped with facilities for ablution, and supervised by someone knowledgeable about the prayer process.

Before Ramadan began, I discussed this arrangement with the school’s administration team and offered the space to them. They included this information in the morning announcements. To my surprise, since Ramadan started, we have had at least ten students coming downstairs daily to pray.

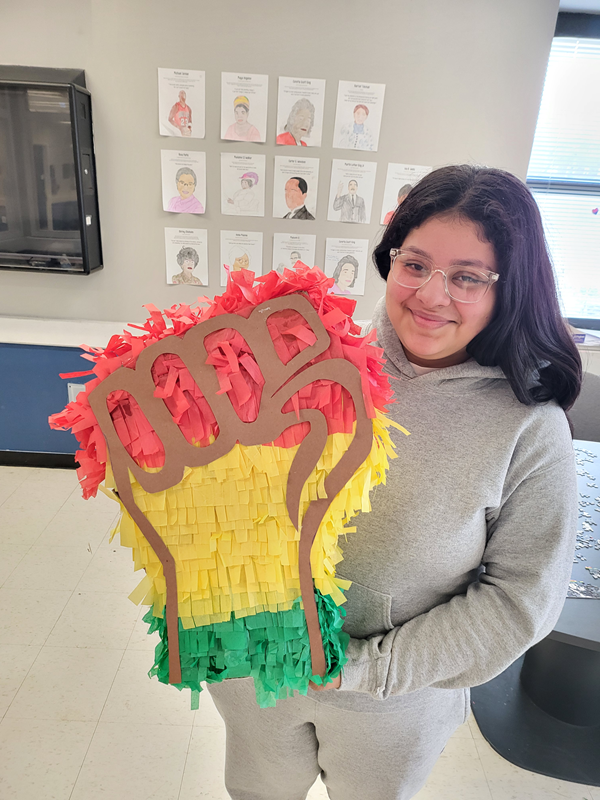

Mehak dedicates a prayer space for Muslim students at J.H.S. 185 and hands out goodie bags for Ramadan.

Can you share what Ramadan means to you personally, and how you celebrate it with family and community?

Ramadan is a deeply personal time when I slow down and focus my energy on strengthening my spiritual and religious connection. I grew up in a modest Islamic family, and since childhood, I’ve always loved fasting and answering the question, “Not even water?” with a proud “Yes, not even water.” Over the years, my family and I have developed a routine of waking up before dawn to have breakfast, or suhoor, and praying together before either going back to sleep or heading out to work. Some days, it’s easier to fall back asleep, while other days can be more challenging depending on when I need to get up for work.

Every year, we decorate our house for Ramadan by putting up moon and star lights, displaying “Ramadan Mubarak” signs, and buying dates to break our fast (iftar). We also give out Ramadan Mubarak goodie bags, and since my niece was born nearly two years ago, we’ve enjoyed watching Ramadan cartoons like “Omar and Hannah” in the background, as long as her screen time allows.

At the end of the month, we celebrate Eid al-Fitr, a festival where we all dress in our best and newest outfits and jewelry, women apply mehndi/henna, we pay our respects to deceased loved ones, and perform the special Eid prayers. Afterward, we enjoy our morning coffee and share meals with family and friends, cherishing the togetherness and joy that this special time brings.

What are some of the challenges you face during Ramadan, and how do you manage them, especially in a work environment?

Growing up, some of the challenges I faced during Ramadan included finding accommodations during lunchtime and explaining to classmates or colleagues that I could not eat. It was important to clarify that my fasting did not mean I was triggered by others eating. As I’ve gotten older, the eating aspect has become less of an issue, and the primary challenge I now face is managing sleep and the fatigue that comes with fasting.

Today, I usually plan ahead and schedule my time off so that I take every Friday off for the month. Since joining The Child Center and at previous jobs, I’ve always communicated with my supervisors about my schedule, letting them know I’ll be off on Fridays as well as Eid. In my religion, Friday is the most sacred day, so it’s important for me to rest and worship. Given the nature of our work, we often have working lunches, so I request to use that one hour to come in later, and if necessary, I am willing to stay later in the evening to complete my tasks. This helps me manage my energy and avoid burnout. As a manager, I offer similar accommodations to my Muslim staff, such as allowing them to adjust their schedules and making a space available for prayer at work.

Before Ramadan begins, I make sure that I complete any high-priority tasks and prepare my team by informing them about the changes during the month. I let them know that my days will be shorter, and my energy levels may be lower, but I will continue to lead by example and make sure both my team and the participants we serve are well taken care of and safe.

How can we be supportive of our colleagues, clients, and community members during Ramadan?

Supporting our colleagues, clients, and community members during Ramadan requires understanding, empathy, and flexibility. One of the simplest ways to be supportive is by just acknowledging that many of us are fasting, which can affect energy levels and routines. Being mindful of these changes can help foster an environment of respect.

For colleagues, offering flexibility in work schedules can make a big difference. One of the major requests I’ve had during Ramadan is to avoid setting up early morning meetings or adding extra meetings to the schedule. Fatigue is a real challenge, and while we may not have the luxury of taking the entire month off, at the very least, letting us work from home once a week or avoiding early morning meetings can help manage energy levels. Additionally, providing a quiet, designated space for prayer or reflection shows support for those observing Ramadan.

For clients, being considerate of meal times or other religious practices is important. If your work involves serving food, for example, offering alternatives or scheduling meals around prayer times can be a thoughtful gesture. It’s also helpful to have a conversation with Muslim colleagues, clients, or community members about how they feel if you are eating around them. While eating around me doesn’t trigger me personally, it may be uncomfortable for others, and having that open dialogue can go a long way in creating a supportive atmosphere.

In the broader community, we can extend our support by participating in charitable acts. Ramadan is a time of giving, so volunteering or donating to local causes can be a great way to engage with and help those in need.

Lastly, it’s essential to provide a space for Muslims to pray. Whether they are colleagues, clients, or community members, a fast is incomplete without the prayers, and having a space available for them to pray is a key form of support.

Ultimately, being supportive during Ramadan is about respecting the observances and challenges of those observing the month, offering understanding when needed, and creating an environment where everyone feels valued and respected.

What is one thing you’d like others to understand better about Ramadan?

It’s not just about abstaining from food and drink; it’s a time to make better habits (such as eating healthier, quitting smoking, or getting up earlier), let go of the bad ones (like road rage, cursing, or gossiping), and, most importantly, it’s the best time to spiritually and religiously reset your mindset. Ramadan offers an opportunity to reflect on one’s actions, improve personal discipline, and develop a deeper connection to faith. It’s about being more mindful of how we treat others and taking steps to become better versions of ourselves.

Mehak Mahmood is a Program Director at our

Mehak Mahmood is a Program Director at our

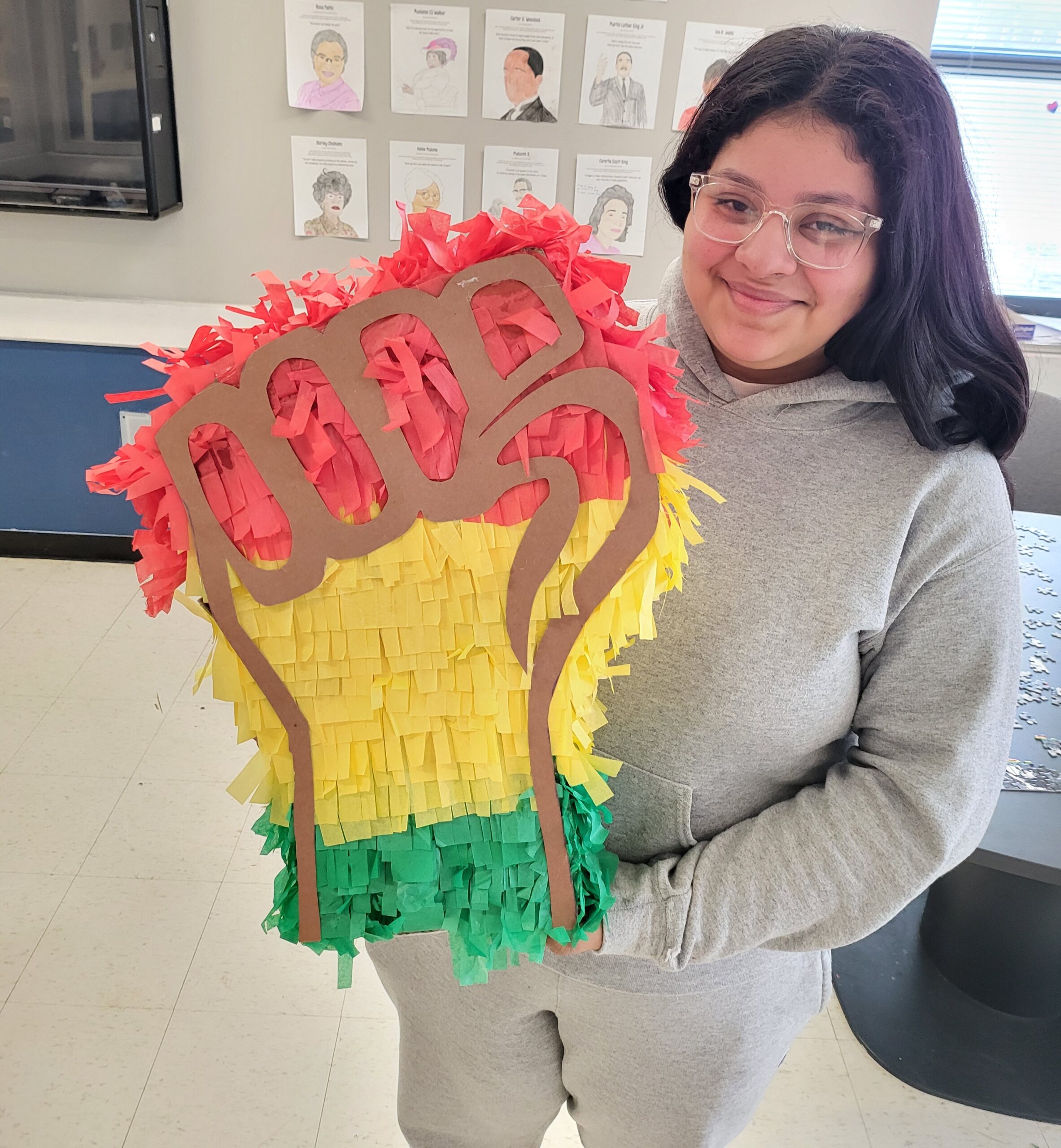

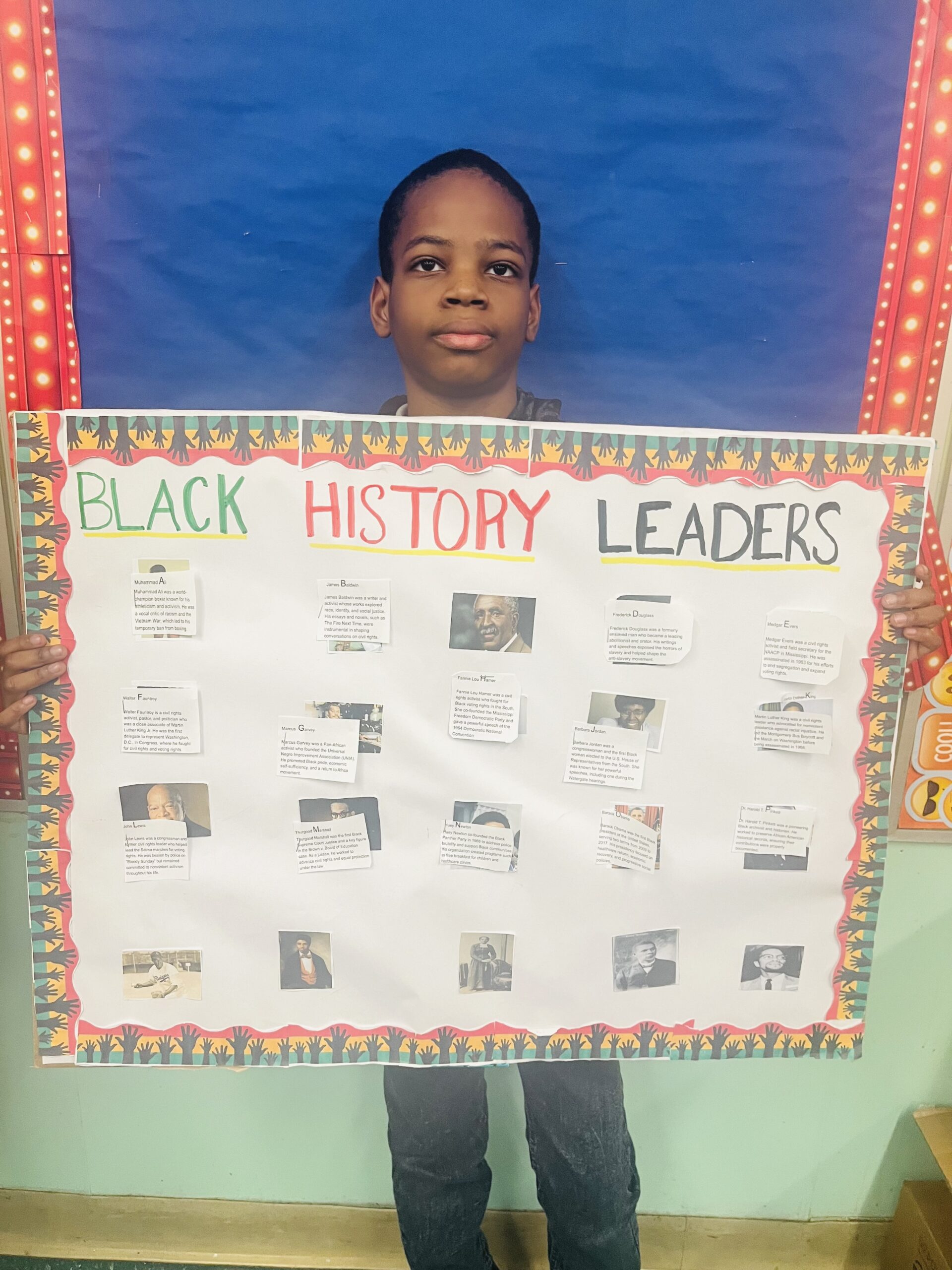

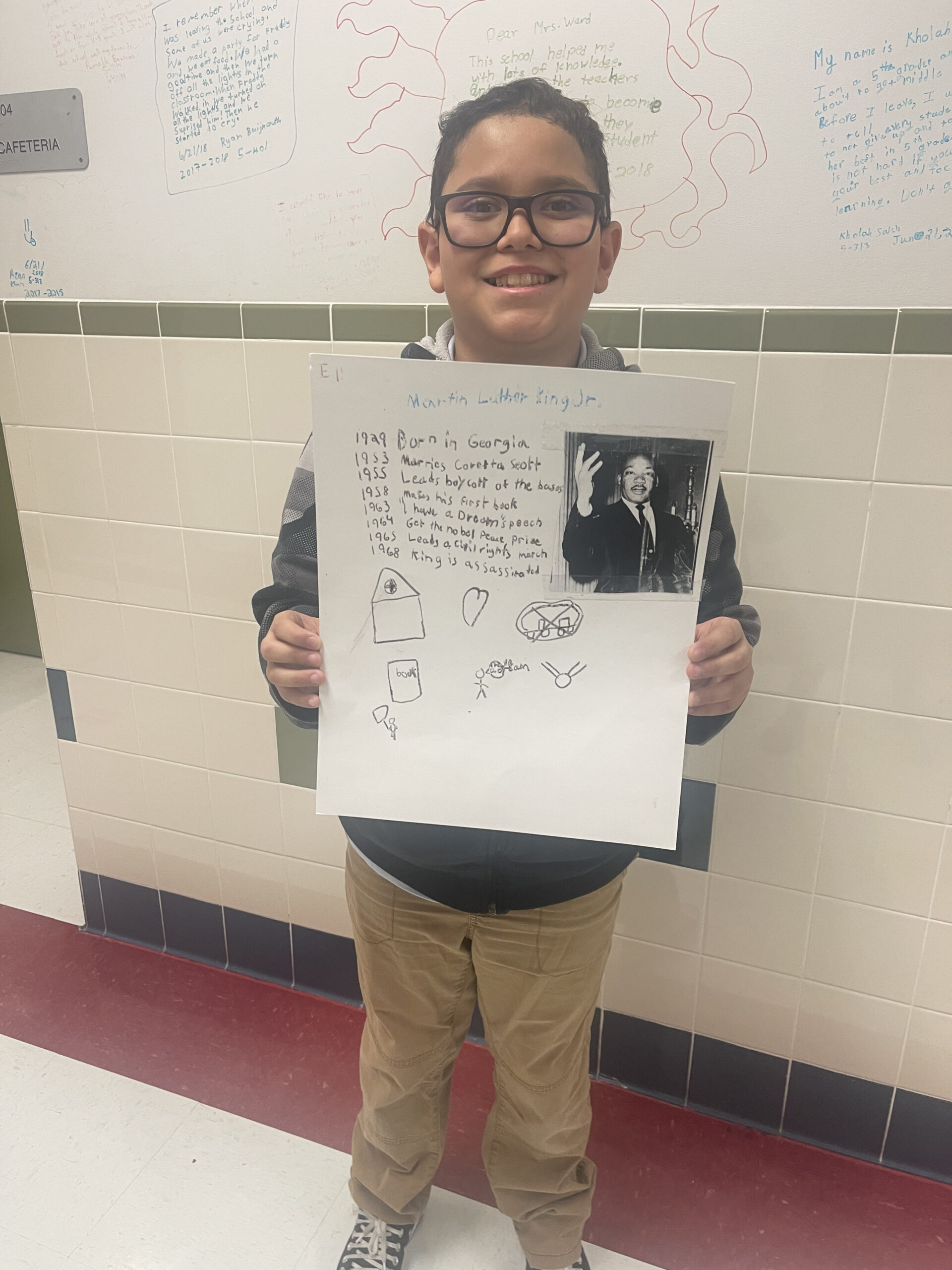

The youth of The Child Center of NY marked

The youth of The Child Center of NY marked

Meet Tahmid and M.D., students at P.S. 182 in Jamaica, Queens, and their parents Mohiuddin and Humaiara.

Meet Tahmid and M.D., students at P.S. 182 in Jamaica, Queens, and their parents Mohiuddin and Humaiara.

You must be logged in to post a comment.