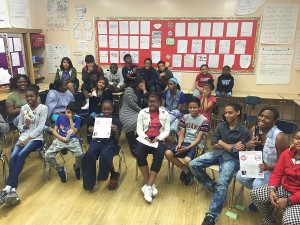

Last month, with the support of one of our Parsons Advisory Board Founders Marc Haken and NYC Councilman Rory Lancman, The Child Center of NY presented a free anti-bullying event at our Parsons Community School (CS) in Flushing. The event was the brainchild not of program officials or community leaders, but rather of middle-schoolers who serve on our Parsons CS’s Youth Council. They said their community needed it.

Last month, with the support of one of our Parsons Advisory Board Founders Marc Haken and NYC Councilman Rory Lancman, The Child Center of NY presented a free anti-bullying event at our Parsons Community School (CS) in Flushing. The event was the brainchild not of program officials or community leaders, but rather of middle-schoolers who serve on our Parsons CS’s Youth Council. They said their community needed it.

They’re not alone: 70.6% of young people in a nationwide study said they see bullying in their schools. Here in our own community, self-harm (like “cutting”) is sadly closer to the norm than an anomaly, and children have even been hospitalized for suicide attempts that have been traced back to bullying.

While that sounds dire, the good news is that we can take proactive steps to reverse this troubling trend by committing to a simple two-pronged approach. First we must connect with students on a personal level to build their awareness of what bullying actually is (many bullies don’t think of themselves as such), what its consequences can be, and how they can get help. Second, and equally important, we as adults need to do our part and make mental health services available—truly available—not only after a crisis occurs, but at a time when crises can be prevented.

Regarding the first part of the equation, we’re on the right track, as a nation and a community. Parenting experts, educators, and community leaders have rightly focused on bullying in all its forms. Schools now make anti-bullying efforts a part of their curriculum; anti-bullying PSAs air on TV shows that kids watch; and the government set up an anti-bullying website.

So why is bullying still a problem?

There are many reasons (bullying in the home, for instance), but chief among them is that we’re talking about children. They are only beginning to sort out all kinds of things, and what constitutes bullying is one of them. Even by middle school, they have very little in the way of a filter and can’t necessarily distinguish between joking around and bullying. As more than one participant at the event noted, sometimes the kid getting bullied is actually laughing along with everyone else. For example, three students at the event shared that every day at lunch, a large group of kids gather to watch students “roast” each other. Two participants make jokes about the other, in an effort to get the biggest reaction out of the crowd. No joke, no subject is off limits. Most days it seems to be in good fun—but there are times when very hurtful things are said: “Some kids don’t stand a chance and have to laugh along with the jokes about them but reveal being hurt later,” one student reported.

This led to a discussion of the potential impact of internalizing teasing—and when put that way, the fine line between teasing and bullying turned into a straight line between cause and effect. The students could begin to understand that seemingly harmless “roasting” could lead to the effect of low self-esteem, self-harm acts like cutting, and, if severe enough, even suicide.

At the schools we serve, we also emphasize service learning and building a sense of community, which are crucial to anti-bullying efforts. The more young people see themselves as part of a community—and themselves as kind, giving individuals—the less likely they are to bully others.

Of course, even as we try to instill in our young people the right kind of values in order to prevent bullying in the first place, we also need to realize that, no matter how hard we work at it, we won’t be able to stop every instance of bullying. That’s why the second prong of the approach—making mental health services truly available to both the bully and the bullied—is vital.

At Parsons, we were creative with our funds and pooled our resources to share a full-time social worker with two other sites. She was awesome. She ran groups and workshops with participants and parents and saw a few students on a regular basis. She worked with them and their parents to help them through challenges that many of us may struggle to even wrap our minds around. Teachers, counselors, and administrators appreciated knowing that when they flagged a student as potentially in need of such services, there was actually a viable option within the school building for him or her to get the help they needed.

But when the social worker left for a position that didn’t require her to split her time among different schools, the summer funding debacles made it difficult for us to replace her, as most social workers want steady, full-time work—not a position in which they possibly won’t get paid for the summer, and has a strong possibility of not being renewed. We ideally should have five social workers for Parsons’ three schools; it shouldn’t be this hard to keep just one. If we are serious about making mental health services available to our children and families, we need to be able to hire and retain first-rate social workers, pay them accordingly, and offer them job security.

Another aspect of making mental health services truly available is bringing clinics into the schools, rather than requiring families to visit clinics out in the community. Time and again we have seen that when we do this, we get better results. That’s because school-based mental health clinics don’t come with the logistical issues or stigma associated with community-based clinics.

We like to assume that when a teacher or school administrator recommends to a parent that his or her child would benefit from therapy with a mental health professional, that parent will immediately contact a clinic, wherever it may be, and bring the child to regular therapy sessions that are paid for by the family’s insurance. In reality, it doesn’t always work like that. I remember one mom whose child had been abused by his father. The child understandably had anger issues, and I recommended that the mom take her son to a clinic for an evaluation and therapy. The mom was a single parent by this point, juggling multiple jobs and kids. Her response was, “I have a one-hour window when I could take him.” The logistical issues are often just too much for the families we serve (to say nothing of the issues of stigma, denial, and insurance). We can impugn these parents’ character all we want—saying they should make therapy for their kids a priority, make sacrifices, do what they need to do, etc.—or we could simply create communities that make it easier to raise our children to become emotionally healthy adults.

As we continue to push for these steps to become the rule rather than the exception, we at Parsons will continue to address bullying on a regular basis through innovative initiatives like last month’s anti-bullying event. We got students in the door with promises of raffles, prizes, and good food—which perhaps made them feel not so self-conscious about attending (”Hey, I’m just coming for the chance to win that $50 Visa gift card!”). They stayed for insightful conversation that yielded ideas they were thinking about as they walked out of it—and hopefully will be for a long time to come.

That, to me, is one of the most vital goals: getting young people to be thinking about these things, in the back of their minds, wrestling with the issues and having the knowledge and guidance to begin to rely on their own good judgment.

Oswald Araujo

Director

The Child Center of NY Parsons Community School Program