A long-time Child Center employee reflects.

By Yolanda Vega, LMSW

Senior Program Director, Head Start Corona

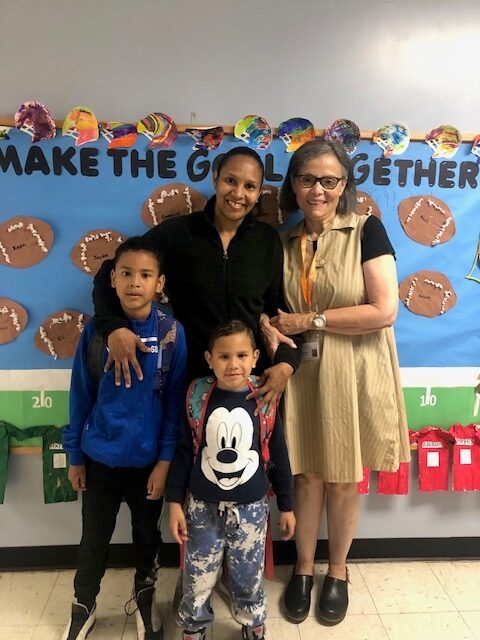

Blog author Yolanda Vega (far right) with Johana (center) and her two children

This is a story about a family who traveled on foot from South America to the United States.

Johana and her partner, José, had their first child in Venezuela. When their first child was one, Johana and José made the decision to leave the country, as economic and political turmoil made it increasingly more difficult to get by. The family then settled in Peru for six years where they welcomed their second child. In 2022, the family made the difficult decision to leave Peru, facing economic hardship and challenges accessing critical services and resources because they were not recognized as citizens; only their baby, who was born on Peruvian soil, was considered a citizen. Traveling by foot through Mesoamerica and Mexico with two small children, Johana and José were determined to make it to the U.S. to provide the best future possible for their family.

I met the family in the fall of 2023, shortly after they had finally made it to the United States. I made a recruitment outreach visit with my co-worker Aaron McIntyre, Corona Head Start’s family service coordinator, to the homeless shelter where the family lives. It is customary for us to conduct these outreach efforts to let families in the community know of our program. On the day Aaron and I met Johana and her young son Misael, I was immediately struck by Johana’s enthusiasm for our program. She wanted to give her child the opportunity to learn how to read and write, as she never learned these skills and knew how hard life was without them. She wanted better for her son and worried that she couldn’t teach him. Aaron and I quickly shifted our attention to speaking with mom rather than showing her pamphlets and forms. We talked, and Johana listened attentively. She was so happy to learn that her son would be eligible, and about all he would learn at Head Start, including, though not limited to, academic readiness, so that he could begin his educational journey at the same level as his peers, and her own lack of knowledge would not hold him back.

Many of our migrant families have made the trip north through very dangerous circumstances, especially when walking through the “frontera,” or the divide between two countries, which many times is filled with gangs and other perilous circumstances. This family, sadly, was no exception. They were robbed in two countries. One time, the robbers pulled out machetes and stated they would slaughter them if they did not give up their cash. Though they had little money with them, who can argue with a machete against their throat?

The family’s journey through eight countries took them through Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and, finally, Mexico, where they surrendered to U.S. immigration officials and, eventually, got on a bus to New York for a 36-hour ride to the Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan, where all migrants are taken upon their arrival to New York. After they completed the process for entering a shelter, the family was given a room with a kitchen and their own bathroom. When the family got to their room, Johana got on the floor to thank God for finally having a bed for her family to sleep on.

After the family had been living at the Manhattan shelter for a year, the NYC Department of Homeless Services moved them to a shelter in Corona, Queens, which is how my team and I came to meet them and enroll Misael in our Corona Head Start program, where he has been thriving.

After assessing Misael’s development in various areas, as we always do with students, our Head Start team worked with Johana to get Misael evaluated through the New York State Department of Education (DOE) Committee for Pre-School Special Education for a suspected speech delay. As Johana awaits word about Misael’s placement for speech therapy (which we can provide on-site through a collaboration with the DOE), Misael is flourishing in the classroom. The class’s language immersion has helped him tremendously. He is able to state his wants and needs to his teachers, which he hadn’t been able to do previously. As a result of being understood, he is much calmer and ready to learn.

The Child Center takes a holistic approach to serving families, and while we care for Misael’s development, we also help the family meet other needs. Both Misael and his brother received backpacks filled with school supplies that they can use in their shelter room, pajamas, sneakers, books, and coats. Through the collection efforts of several of our teachers, Johana received much-needed shoes, a coat, and other clothing.

Johana is extremely grateful for all of what she has gained from being connected to our program, and she often comes to my office to keep me posted on the jobs she and her husband have taken. Johana has found work in offices, though she doesn’t find openings as often as she would like. Her husband, who is a food delivery person on an e-bike, is busy working seven days a week. On a recent weekend afternoon while I was in my car waiting for the light to change, I heard my name, “Miss Yolanda,” and as I turned my head to face where the voice was coming from, I saw that it was Misael’s dad, who was waving at me. I blow my horn, and wave “hello.”

It is moments like these, when I run into clients, and they seem so genuinely happy to see me, that confirm why I continue to work for The Child Center of NY. The mission drives right into my heart, and I often think of that professor who said when I wanted to join the Peace Corps, why are you doing this when you are so needed right here where you are! Indeed, I love living and working in the communities I serve as it confirms: The Child Center of NY strengthens children and families with skills, opportunities, and emotional support to build healthy, successful lives.

Yolanda Vega has worked for The Child Center of NY for 22 years, first as a part-time Head Start social worker, followed by promotions to assistant director of early childhood programs and director of one of The Child Center’s Prevention and Family Support programs, and now as the director of our Corona Head Start.

You must be logged in to post a comment.